The Family Nobody Wanted Where Are They Now

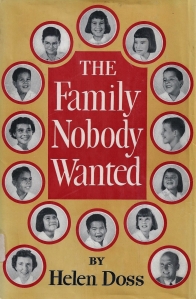

The Family unit Nobody Wanted by Helen Doss ~ 1954. This edition: Little, Dark-brown & Company, 23rd printing. Hardcover. 267 pages.

The Family unit Nobody Wanted by Helen Doss ~ 1954. This edition: Little, Dark-brown & Company, 23rd printing. Hardcover. 267 pages.

My rating: half dozen/10

Well, this was an interesting read, and I'm nevertheless trying to decide what my personal reactions really are.

On the surface it is a simple feel-expert memoir about a young childless couple adopting twelve children in the 1940s and 1950s, but at that place are deeper currents to the tale, peculiarly from a half-century later on perspective. In item, in that location is a damning sub-text of racial intolerance which is very much a function of why and how this family came together.

I didn't yearn for a career, or maids, or a fur coat, or a trip to Europe. All in the globe I wanted was a happy, normal little family. Mayhap, if God could arrange it, Carl and I could accept a boy first, and after that, a picayune girl.

God didn't arrange information technology.

In fact, as our doctor regretfully informed us, Carl and I couldn't take whatever children of our own. No children, no sticky fingerprints on the woodwork, no childish tears and laughter, no pocket-size beds in the other bedroom. Merely barren, empty years, stretching aimlessly into a lonely future…

So Helen'southward husband Carl, driven to distraction past his wife'southward continual bemoaning of her barren futurity, suggests that they adopt a baby. Helen loves the thought, and the two optimistically prepare a room and trot off to the nearest orphanage, where they larn that it isn't quite equally elementary as all that. Most of the babies in the orphanage were simply not available, being simply in temporary care, or waiting for relations to take them in, and the adoption agencies which are the next resort are not particularly helpful either. Helen and Carl are informed that waiting lists are years long, and that each babe must match its potential parents perfectly in indigenous makeup and family background. And of class the parents must be financially stable, likewise equally sterling characters in all other aspects.

Carl and Helen are certain their characters are good, but the money matter is definitely an issue, and the waiting list state of affairs seems cruelly stressful. And then they prepare aside their ideas of forming a family and instead decide to pursue other interests. Both enroll in college, Helen to study literature and writing, and Carl to pursue a long-held dream to become a Methodist government minister. And and so, miraculously, one more endeavor at adoption through an agency results in a beautiful blue-eyed baby boy. Helen is ecstatic; Carl more reserved. They can barely feed themselves, so this new addition is a challenge in more ways than 1.

Young Donny thrives and grows, and all is well for a while, until Helen starts to brood over the loneliness of the just child. "If but he could have a fiddling sis…" Merely another kid is an impossibility, declares everyone they contact. "Just be happy you managed to get the one." Unless, of class, they would consider a mixed race child. Lots of those were languishing in adoptive limbo, and, 3 years subsequently Donny'south adoption, Filipino-Chinese-English-French Laura joins the family unit. And, only two months afterward, delicate and sickly Susan, undesirable considering of her weak constitution and a tumorous red birthmark on her face.

Helen is nonetheless thrilled, though she finds 3 children something of a challenge, but all 3 thrive, and Helen starts thinking again. Maybe just one more, a brother for Donny…

Eventually, with increasingly strident resistance from Carl, Helen collects a round dozen of children, six boys and six girls. She writes about the family's experiences, and the tragedy of mixed race children being seen as undesirable by families otherwise drastic to adopt a babe; even though the Filipino, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Malayan, Burmese, Spanish, French and American Indian children she and Carl eventually acquire are accepted by family and neighbours, a abiding refrain is "As least they aren't Negro!" Carl and Helen do attempt to adopt a part-black kid from a German orphanage, kid of black American GI father and a German mother, but the transaction is strangled by red tape; their families and friends are loudly song in their relief, and one of the most passionate chapters in the book strongly condemns this mental attitude, and addresses the degrees of racism inherent in American society, and its effect on innocent children along with its office in much greater societal ills.

Helen and Carl come across as truly sincere in their attitudes that color means aught, and that human being is human; Helen starts writing articles about their "United nations" family unit, and the Dosses catch popular attention, being interviewed, photographed and featured on radio and television, equally a kind of shining example of American credence and tolerance, though in reality the very beingness of their family group has come about through blatant American racial discrimination. These are, after all, the children that nobody wanted.

The book ends only twelve years later on that commencement baby, Donny, is adopted, and the tone is happily optimistic, but there are undertones that possibly all may not be then well in time to come. Carl is a reluctant participant in the continual enlargement of the Doss family, though he is very willing to tout its benefits for interviewers; Helen persists in collecting children in the face of Carl's outright "No more" plea, time and time once again. The news that the Doss marriage ends in divorce in 1966, twelve years afterwards the publishing of this bestselling book, comes as no surprise, though it is sad; ane hopes that the children – some at that time well into adulthood, one must admit – weathered their family unit breakdown with a minimum of trauma, though one doubts that would completely be the example.

Knowing several cross-culturally adopted children who now, equally adults, are seeking diligently to reconnect with their birth parents' heritage, I wonder what happened to those twelve children as they grew upwards, and what they each personally made of their inclusion in this unique family unit, and of the publicity which their parents' outspoken willingness to discuss their adoptive choices attracted.

I do recall, both from the tone of Helen Doss's memoir, and from other reports on the Doss family I read on the net, that their intentions were, in one case they started adopting, just the best. And, besides, I practice tend to think that children deserve a loving family versus being institutionalized, and that if the only fit possible is cross-cultural, and so be it. If it were more widely accustomed (equally it wasn't in the 1940s and 1950s) then at least the "novelty factor" would not be such an issue.

I've tagged this postal service with a "organized religion" designation, considering it is likewise very credible that Helen and Carl Doss were motivated in a great office by their Christian religion. Carl Doss is quoted equally saying that

…The whole idea of Christianity is radical (a)nd the whole idea of commonwealth is radical. Recall how actually it is to say that all men are created equal, and that all men are brothers – and that the individual is important!

Conflicted as Carl seems to be by his married woman's conquering of child after child, once they are brought into the family he apparently embraces his fatherhood fully, beingness as full of latent paternal affection as he is of "radical" Christian ideals.

A thought-provoking memoir, and, as I said, a bit uncomfortable to consider more deeply, given that a whole lot must have been left out. Though I was interested and pleased to see that Helen Doss was very frank virtually her own motivations of needing children to "complete" her idea of truthful womanly fulfillment; the ideal of a happy, multi-racial family group seemed to develop every bit her circumstances changed.

I did my usual await-around the web, and was interested to come across how highly this book was rated on Goodreads; a big number of people apparently read and loved it in their schoolhouse years; the reviews are by and large quite glowing.

It is very readable, and provides a truly fascinating (though superficial) glimpse into the mid-20th Century's social dilemmas and attitudes towards both adoption and racial and interracial societal division lines. It is also often very funny; Helen Doss'southward anecdotes of her children's doing are downright ambrosial, and well targeted at the sentimental readers who have obviously embraced it equally a "sweet tale". It is a sweetness tale; it is also an indictment of the bitter evils of racial discrimination; and a strong advocate of true Christian behaviour; and a revealing portrait of a wedlock not without deep personal conflicts, despite its publically positive façade.

For more on the Doss family, these links will be good starting points.

Helen Doss – Obituary

Adoption Topics – The Family unit Nobody Wanted

Source: https://leavesandpages.com/2013/09/06/review-the-family-nobody-wanted-by-helen-doss/

0 Response to "The Family Nobody Wanted Where Are They Now"

Post a Comment